In June 2016, Dave Larson sat in his boss’ office at Triton Energy LLC, in Waterloo, Indiana, filling out a worker’s compensation form. The day before, he’d taken a nasty fall from a ladder. He’d also begun to suspect his employer was involved in a federal biofuels program fraud scheme. He told Triton CEO Fred Witmer he might talk to the Environmental Protection Agency.

According to Larson, Witmer listened silently, then casually reminded Larson of his alleged close connection to a high-ranking state elected official. He reached into his desk as if to get another form. Instead, he pulled out a handgun, laid it on the desk with the barrel pointed straight at Larson, and said, ominously: “People can disappear. Their families can be harmed.”

Larson believed him.1 He still does. Almost five years later, Larson doesn’t tell people where he lives. He makes phone calls from restricted numbers and legally carries a high-capacity handgun.

Witmer went to federal prison after being convicted in July 2017 of bilking American taxpayers of more than $60 million – one of dozens of scammers who perpetrated what a former EPA chief investigator calls “the most significant series of frauds on the environment ever prosecuted.” After serving more than three years of a 57-month sentence, he was released last September.

Collectively, Witmer, others who got caught and those who got away with it collected billions in federal tax credits through a well-intentioned program to reward producers of renewable fuels from plant-based stock. The EPA’s investigation is ongoing, with more biofuel scam convictions as recently as last fall. And as the Biden administration considers new proposals to harness biofuels to counter the climate crisis, the saga of biofuels fraud is a cautionary tale that reads like a spy thriller.

Dave Larson was born in the early 1960s and grew up in the New York-New Jersey area, the son of a Bell Labs scientist. From childhood he tinkered with machines and engines, taking them apart and putting them back together again.

By his forties, Larson had built his own biodiesel processor in his garage, using a hydronic boiler and discarded 50-gallon oil drums. Soon he ran a small fleet of refurbished cars on filtered used vegetable oil he distilled himself, scouring message boards to learn brewing techniques while collaborating with other amateur fuel makers.

Some biofuel enthusiasts, like Larson, were driven to do their part to fight climate change – “a way of sticking it to corporate America and fighting Big Oil,” he said. Others were survivalists prepping to live off-grid. Then there were entrepreneurs hunting for the next big investment in clean energy.

The federal government realized people like Larson were on to something. The Renewable Fuel Standard program, or RFS, begun in 2005, was the rare federal program praised by leaders of both parties. President George W. Bush said the expanded program would give “future generations a nation that is stronger, cleaner and more secure.” House Speaker Nancy Pelosi called it “a moment of real change” that would reduce oil imports, cut production of greenhouse gases and significantly improve auto efficiency.

But for the program to be effective, it had to be done on a large scale – something that couldn’t be done by the backyard biofuel community alone. Through the RFS, the government offered lucrative subsidies and tax credits to companies to convert commodity crops like soybeans and corn, along with used fryer oil and other food waste, into renewable fuels. The most common biofuel is corn ethanol, which is added to most gasoline sold in the U.S.

When the RFS was expanded in 2007, Larson and his friends were self-taught experts in what promised to be a multi-billion-dollar industry. “I believed in it and I knew how to do it,” he said. “This seemed like a way to fight the problem and make money.”

Much as it did with other early biofuel enthusiasts, the nascent industry gave Larson the incentive to make his hobby into a career. The program also encouraged experimentation beyond used fry oil.

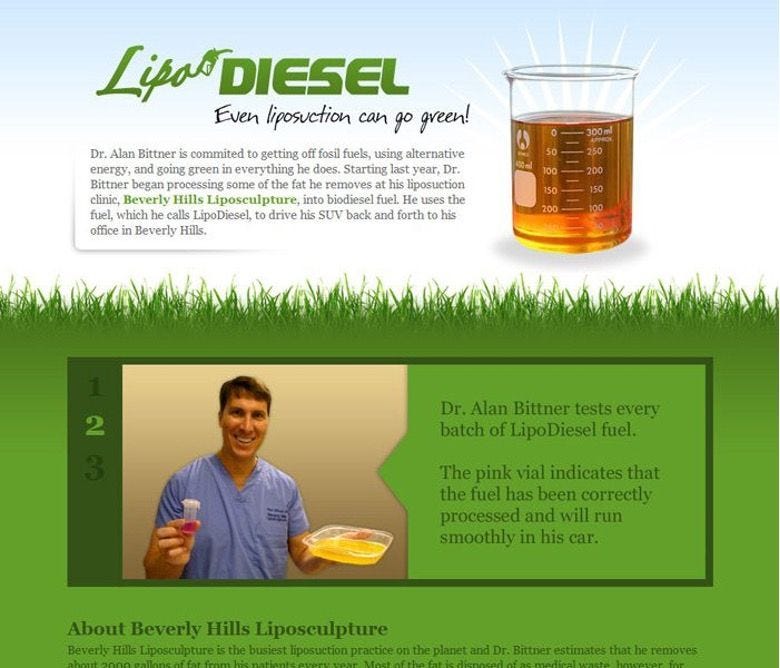

The most notorious example was Dr. Alan Bittner, a Beverly Hills plastic surgeon who used fat from his liposuction patients to power his SUV. Bittner eventually fled the U.S. to avoid prosecution on an array of charges, including letting his unlicensed girlfriend perform surgeries. But there were plenty of less nefarious examples of experimentation, including a town in England that converted the carcass of a beached whale into fuel.

Image

Screenshot of Dr. Alan Bittner’s now-deleted LipoDiesel website.

But aside from such outlandish examples, 2005 was U.S. biofuel’s moment. To promote clean energy, Woody Harrelson drove around the country in a bus powered by hemp oil. Pearl Jam and Norah Jones demanded tour buses that ran on biofuel. Willie Nelson launched BioWillie, his own vegetable oil biofuel brand.

Home brewers like Larson still preferred used fryer oil. It was easy to process, burned clean and, before the RFS was signed into law, was readily available at thousands of American fast-food restaurants.

But the launch of the RFS program brought big companies into the biofuels market, driving up the price. That sparked a crime spree, with thieves trying to steal used oil and grease that not long ago had been thrown away.

The thieves used bolt cutters and blow torches to break into grease traps, offloading their haul into waiting tanker trucks. In Houston, fry oil theft was so rampant, it earned the nickname “Fat City,” and attorney Jon "The Grease Lawyer” Jaworski made a name for himself defending people accused of stealing it.

• • •

Dave Larson’s first foray into the newly professionalized biofuel industry ended up being a job with a Florida company he came to believe was actually a grease theft ring.

On his first day on the job in 2010, Larson rode on a company truck, picking up barrels of grease from fast food restaurants. Larson figured his new employer had contracts with the hamburger joints where they stopped. But Larson said he soon realized they were stealing grease from containers belonging to rendering companies, which add it to livestock feed. Larson quit, literally jumping off the truck in the middle of his shift.

What Larson, the EPA and most everyone else did not know was that the company Larson briefly worked for apparently was part of a growing underground of shady operators exploiting the new industry. RFS was a feel-good, bipartisan program that would address climate change, foreign oil dependence and slumping farm prices, so no one put much thought into how it should be regulated.

“Even before the RFS, alcohol fuel programs in Brazil and the United States have been susceptible to fraud,” said Jeffrey Manuel, associate professor of history at Southern Illinois University, Edwardsville, who is co-authoring a book on the history of biofuels in the U.S. and Brazil. Decades before the tax credits started flowing, Michael Reagan, former president Ronald Reagan’s oldest son, was named by the FBI in an investigation of an ethanol company that took investors’ money but never produced fuel. The FBI later cleared him, saying he was a victim of the scam, not a perpetrator.

Baked into the RFS were biofuel production incentives called RINs, for renewable identification numbers. The EPA required that a 38-digit number track each gallon of corn ethanol or biodiesel as it moved from producer to refiner to point of sale. Corn ethanol RINs stayed with the product until it entered a gas tank. But biodiesel from soybeans, and advanced biofuels derived from crop waste, were assigned RINs that could be stripped away and sold separately as tradable credits.

An oil refiner who didn’t blend the required amount of biodiesel into its product had to buy RINs to make up the difference or pay big fines. To defraud the program, early criminals started by negotiating on a price with a buyer like an oil refiner. Then they fabricated a host of faux 38-digit numbers and supposedly shipped the biofuel off to be refined. No fuel was bought or sold, but the responsibility for the authenticity of the RINs numbers lay with the buyer. If the RINs were found to be fake, the buyer had to replace the phony numbers.

In 2009, Rodney Hailey claimed he was producing biofuels at his own Baltimore plant, generating $9 million in credits from the sale of 35 million RINs representing 23 million gallons of fuel. But he never produced a drop. His plant never existed.

He spent the money on a fleet of luxury cars ranging from Ferraris to Lamborghinis and parked the exotic cars on the street in his middle-income suburb, raising his neighbors’ suspicions. When the EPA started investigating, he Googled “biofuel plant” and sent the pictures to the agency as proof of his operation. At the federal trial in 2012 in which Hailey was convicted on 42 counts of wire fraud, money laundering and Clean Air Act violations, the prosecutor said: “There is no prize for being the least clever criminal on your block.”

Amanda Peterka of Environment & Energy News was among the first to report on the early waves of RIN crime. The first big case she covered was Absolute Fuels.

In 2013, Jeffrey Gunselman, owner of Absolute Fuels, in Lubbock, Texas, was convicted of wire fraud and money laundering for selling more than $40 million in fake RIN credits for biofuels he never produced. Like Rodney Hailey, he had a taste for luxury cars – buying a Bentley, a Mercedes-Benz, a Lexus, a Cadillac and a Shelby Cobra, along with a decommissioned U.S. Army tank and a Gulfstream jet. He was sentenced to 15 years and eight months in prison.

Reilly’s reporting led her to more biofuel crimes across the country, and a pattern started to emerge of organization and coordination between fraudsters.

“There were copycats and they were getting more outlandish as time went on,” Reilly said. “I remember them being very Mafia-like.” Scott Irwin, an agriculture economist at the University of Illinois, said he has always “half-expected the real Mafia to be involved in RIN fraud,” given organized crime’s connections in the waste management industry.

Dave Larson left Florida in 2011, disillusioned but not defeated. He headed to the Corn Belt, hoping to hook up with a legitimate biofuel company to advance his career. By chance, a stop in Indiana to look for biofuel for his pickup led to Triton Energy, which had just been started by Fred Witmer and his partner, Gary Jury, the company’s chief financial officer.

As Larson filled up his truck, the men talked shop. Larson immediately liked the two partners. They seemed to be the embodiment of Midwestern values: “They always presented themselves as [having] heartland values and their only interest was saving the environment,” Larson said.

Witmer showed Larson around and said his plant would produce a million gallons a month when fully operational. Larson impressed Witmer by pointing out a flaw in the plant’s piping. He suggested a simple fix that would allow Triton to produce an extra 10,000 gallons a day. Then he asked Witmer how much he owed him for the fuel.

“Nothing,” Witmer said. “All Triton Energy employees fill up for free.” He hired Larson on the spot.

Like a lot of other biofuel processors, Triton had developed a formula that used animal fats, vegetable oil and alcohol. But Larson said Witmer boasted that they also added a secret, proprietary chemical catalyst to the formula that boosted yields and made their fuel the best on the market. What Triton lacked was a consistent supply of feedstock. Larson’s new job would be to travel from farm to farm to get contracts to buy stillage, a distilling residue left over after ethanol is made.

In 2012, a year after Larson was hired, then-Rep. Mike Pence ran for governor. Pence barnstormed the state in a cherry-red Chevrolet pickup, on what he dubbed the Big Red Truck Tour. Eleven days before the election, Pence held a rally at Triton Energy .

Image

Mike Pence and Fred Witmer at Triton Energy rally. Photo courtesy Dave Larson.

Standing on a hay bale in the truck bed, the soon-to-be-governor and future vice president posed for pictures with Witmer and said: “Triton Energy is a model for what my platform wants to build in Indiana – strong jobs and innovation.”

Like other federal agencies, the EPA has its own police arm, known as the Criminal Investigation Division. Special agents carry weapons, go undercover and make arrests. Former division director Doug Parker, who spent 25 years chasing criminal polluters, said some agents called themselves “the power behind the flower” in a nod to the agency’s logo.

EPA agents don’t just deal with pollution, they also have expertise in banking and tax law. Cases can take years, as agents work to identify chemicals and pollution in a way that can stand up in court. When RIN fraud erupted, they knew exactly what they had on their hands, even if they didn’t have the power to change a program authorized by Congress.

“EPA was never set up to be a market regulator; that wasn’t the agency’s expertise,” Parker said. “Every time we brought federal prosecutors a RIN fraud case, we told them the ‘baby was ugly’ – meaning the RFS program was deeply flawed.”

In the beginning, Parker and his agents were on defense, chasing only “knucklehead fraud,” like Rodney Hailey’s case. By parading the likes of Rodney Hailey and Jeffery Gunselman before the higher- ups at the Department of Justice, Parker secured a mandate to create a RIN fraud task force made up of senior agents, criminal analysts, attorneys and regulatory experts to analyze the vulnerabilities in the RFS program.

“When we figured out that these were transactional crimes, that [tax] credits needed a buyer and a seller, both of which were in on the con, we could better chase the crooks,” Parker said. “My focus became forming a national anti-fraud task force. And the team kicked ass.”

By 2013, about one in 10 of the EPA’s criminal investigators was looking at RFS fraud. They analyzed huge files of data to look for patterns and started assembling a list of companies they suspected.

Back in Indiana, Dave Larson had grown alarmed over developments at Triton. One suspicious errand included delivering a secretive “corn product” hauled in the false bottom of a delivery van to refiners in Wisconsin. “Drivers were told if stopped by Wisconsin DOT [Department of Transportation] not to say anything about the ‘additive’ and to call Witmer immediately,” Larson said.

After a road trip, Larson noticed the engine on his biofuel-converted pickup was skipping. He’d been burning Triton’s proprietary renewable diesel. But after 800 miles, a strange, yellow-colored waxy substance completely gummed up the engine, eventually killing it.

Larson discovered that the secretive catalyst Witmer touted was an enzyme used in soy diesel, with “added secret ingredients.” It was not suited for the heavier fat content of biofuels derived from waste and manure. Triton’s biofuel was essentially waste corn oil that, over time, would wreak havoc on any engine.

“They had snake oil and they knew it,” Larson said. “Their ‘renewable diesel’ was nothing more than corn oil pushed through a filter bag.”

According to the EPA’s Doug Parker, the failure to generate a commercially viable biofuel at scale drove scores of other producers to commit felony fraud to keep their lucrative government credits pouring in. “Instead of brewing biofuels,” Parker said, “they were cooking the books.”

Perhaps the biggest RFS scam involved the cultish Mormon sect called The Order. (Not to be confused with the neo-Nazi group that in 1984 assassinated a Jewish talk-show host in Denver.) The 2,000-member sect had for years used accounting tricks to avoid paying taxes, even as they feigned poverty to defraud government welfare programs like food stamps. They called the practice “bleeding the beast.”

Worth $150 million, the Order owned dozens of businesses, from California casinos to Nevada cattle ranches. The group also owned a big biofuel plant built by Jacob Kingston, the 40-year-old great-nephew of the sect’s founder, on land the cult owned on the Idaho-Utah border.

But the plant failed to produce true biofuels at a profitable scale. A chance meeting between Jacob Kingston and Lev “The Lion” Dermen offered Kingston a lifeline. An Armenian immigrant who settled in Los Angeles at age 14, Dermen took ownership of dozens of truck stops and gas stations through illegal backroom deals, skirting gasoline tax laws, shielded by what he called his “umbrella” – corrupt law enforcement officials on his payroll.

Dermen showed Kingston how to use what the EPA’s Parker called “ghost loads.” Fraudsters filled tankers and trucks with liquid and forged logbooks to make it look as if they were shipping true biofuels. They raked in a fortune, spending it on mansions and exotic cars, until 2016, when IRS agents raided Kingston’s offices in Salt Lake City.

Kingston was indicted for biofuel fraud to the tune of $450 million but flipped on the Lion for a lighter sentence. In 2019, he, his wife, his brother and his mother pleaded guilty to multiple charges. Last May, Dermen was convicted for defrauding taxpayers of $1 billion. He faces 20 years in prison, although sentencing has been delayed by the Covid-19 pandemic.

“I always thought that Lev thought the Kingstons were dupes, and was way more sophisticated,” said Jesse Hyde, who reported on the Kingston case for Bloomberg News. “I wouldn’t be surprised if [Dermen] spotted some other operations and thought they are the bridge for me to get all this cash.”

Was Triton Energy one of those operations?

“Of course, Witmer knew Lev and Kingston,” said Dave Larson. “I heard them talking on speaker phone in Witmer’s office.” On Witmer’s desk, he said, was a notepad with “Dermen” and a phone number written on it.

Weeks after spotting Dermen’s name, Larson fell from a ladder at the Triton plant, severely injuring his teeth and jaw. That same day, he also inhaled a mysterious white powder – the secret proprietary catalyst Witmer had talked about. Doctors have been unable to figure out what the chemical was but fear the multiple sclerosis-like symptoms Larson soon developed will plague him for the rest of his life.

According to federal charges filed in September 2016, Witmer and his partner Gary Jury sold off much of their corn oil brew as an ingredient in fire starter logs and asphalt. The indictment said Witmer had stolen $56 million from U.S. taxpayers through biofuel and tax credit fraud. He pleaded guilty, was sentenced to 52 months in prison and agreed to pay back the money. But Larson says he later learned Witmer ultimately had to pay back a tiny fraction of that amount. Jury also pleaded guilty, was sentenced to 30 months in prison and released in May 2019.

The fallout from the criminal cases has set the advanced biofuel industry back decades. Big energy industry players have completely quit the field. Dozens of legitimate, clean energy companies went belly up after unknowingly buying fraudulent credits from companies like Triton. Others went bankrupt after licensing failed biofuel formulas like the one Witmer concocted that never delivered.

But one biofuel not only survived: It thrived.

Propped up by a federal mandate for blending ethanol into gasoline, 40 percent of America’s corn – a commodity for which farmers have gotten more than $71 billion in federal subsidies since 2005 – is eventually converted into ethanol. But cheap energy from the natural gas fracking boom, a glut of product and the cratering of transportation fuel demand from the Covid-19 pandemic has put even the corn ethanol sector on life support. (During the presidential campaign, candidate Joe Biden wooed Iowa corn farmers by pledging continued support for the ethanol mandate.)

RIN fraud hasn’t stopped. In October, the two owners of Pennsylvania-based Keystone Biofuels were sentenced to prison for fraudulently claiming more than $9 million in tax credits. “The only green resource these two cared about was money, and they told lie after lie to perpetuate their fraud,” said the FBI agent in charge of the bureau’s Philadelphia field office.

And the environmental consequences of America’s biofuel program have been significant.

Spurred by the prospect of federal subsidies, American farmers have plowed under more than seven million acres of land to plant corn and soybeans, sending the equivalent of the annual carbon emissions from six million passenger vehicles into the atmosphere. Runoff from the heavy use of chemicals to grow the crops has polluted waterways across the Midwest with toxic nitrates and pesticides.

To date, no one has officially calculated the carbon reduction benefits lost by the advanced biofuels that were never produced due to widespread fraud. Any attempt to measure the damage would lowball it, because an unknown number of cases have never been prosecuted.

“It is the most significant series of frauds on the environment ever prosecuted,” retired EPA investigator Doug Parker said. “The government to date has charged [fraud of] more than $1 billion and put people in jail for a couple of hundred years when you add up the sentences. And if you’ve charged $1 billion then there’s X number of billions out there.”

Now new Biden administration proposals to harness agriculture to battle the climate emergency could repeat the same well-intentioned mistakes made by the RFS. Biden has proposed putting $1 billion into a “carbon bank” that would pay farmers who adopt conservation practices that supposedly sequester carbon – but the jury is still out on how effective such practices are.

Jeffrey Manuel, the Southern Illinois University biofuels historian, said he believes carbon markets “will certainly be vulnerable to fraud like the RFS has been.”

“Any time a great deal of money – public and private – flows into an agricultural boom with little oversight, there will be temptation for some people to cheat the system,” Manuel said. “As I understand the science of carbon sequestration, a great deal of testing and long-term enforcement will be necessary to ensure public money goes to long-term removal of carbon from the atmosphere.”

The day before Fred Witmer was to report to federal prison, Dave Larson called his ex-boss. He recalled the conversation:

“Tell me how you got such a good deal,” Larson said. “What happened to all the money?”

Witmer said nothing. Larson asked if he’d ever see any of the money he was owed for honestly earned commissions.

“Let’s just say everyone is going to get paid once some time elapses,” Witmer said.

“Do you have the money hidden somewhere?” Larson asked.

Witmer didn’t answer, then once again reminded Larson of his alleged political connections. Larson started to ask another question, but Witmer cut him off.

“You have family,” Witmer said. “Think about that.”